The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution is a consequential amendment protecting several civil and political rights of the people. The Constitutional Amendment establishes citizenship rights, equal protection under the law, and prohibits state and local government from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, which essentially makes Bill of Rights protections applicable to the states. The Constitutional Amendment restricts apportionment in United States Congress for denial of suffrage. The Fourteenth Amendment also disqualifies from public office those who engage in insurrection or rebellion against the United States government, and ensures the validity of public debt.

What is the Fourteenth Amendment in simple terms?

The Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States says all persons born in the country are United States Citizens and prohibits unequal applications of laws or denial of property, life, or liberty without a fair hearing or Due Process. The 14th Amendment provides for Incorporation of the Bill of Rights against the states, addresses apportionment in the United States Congress for states engaged in disfranchisement, and also affirms the validity of United States debt while rejecting debt of the Confederate States of America incurred during the American Civil War. Persons who have engaged in insurrection against the government are prohibited from serving in government pursuant to this amendment.

WHAT IS THE TEXT OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION?

U.S. Const. Amend. XIV. CITIZENSHIP; PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES; DUE PROCESS; EQUAL PROTECTION; APPORTIONMENT OF REPRESENTATION; DISQUALIFICATION OF OFFICERS; PUBLIC DEBT; ENFORCEMENT.

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

WHAT IS THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT IN THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION?

Although the Preamble declared the Constitution of the United States was written with the intent “to form a more perfect Union,” the Union has been divided since 1776 into states in which slavery was legal and illegal. The “Privileges and Immunities clause” in Article IV of the Constitution thus did not apply to everyone living in the United States prior to the enactment of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

By the time of the Civil War, congressional Republicans on Capitol Hill had generally accepted the abolitionists’ ideals that slavery and its concomitant disabilities needed to end immediately. Carter, William M., Race, Rights, and the Thirteenth Amendment: Defining the Badges and Incidents of Slavery, 40 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1311 (2007). Even conservative Democrats in the House and United States Senate realized slavery was inevitably at its end, and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments were designed to enforce abolition and achieve equality. Added to the Constitution in December of 1865, long after the Union’s military victory, it fulfilled the promise of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation that emancipated slaves in Confederate states.

When was the 14th Amendment legally ratified?

On June 8, 1866, the United States Senate passed the Fourteenth Amendment. It was ratified two years later, on July 9, 1868. The Amendment granted citizenship to all persons “born or naturalized in the United States,” including formerly enslaved people, and provided all citizens with “equal protection under the laws,” extending the provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states. It further authorized the government to punish states that abridged citizens’ right to vote by proportionally diminishing their representation in Congress. It likewise banned “engag[ing] in insurrection” against the United States, and prohibited those who did from holding any civil, military, or elected office without the approval from two-thirds of the House and United States Senate.

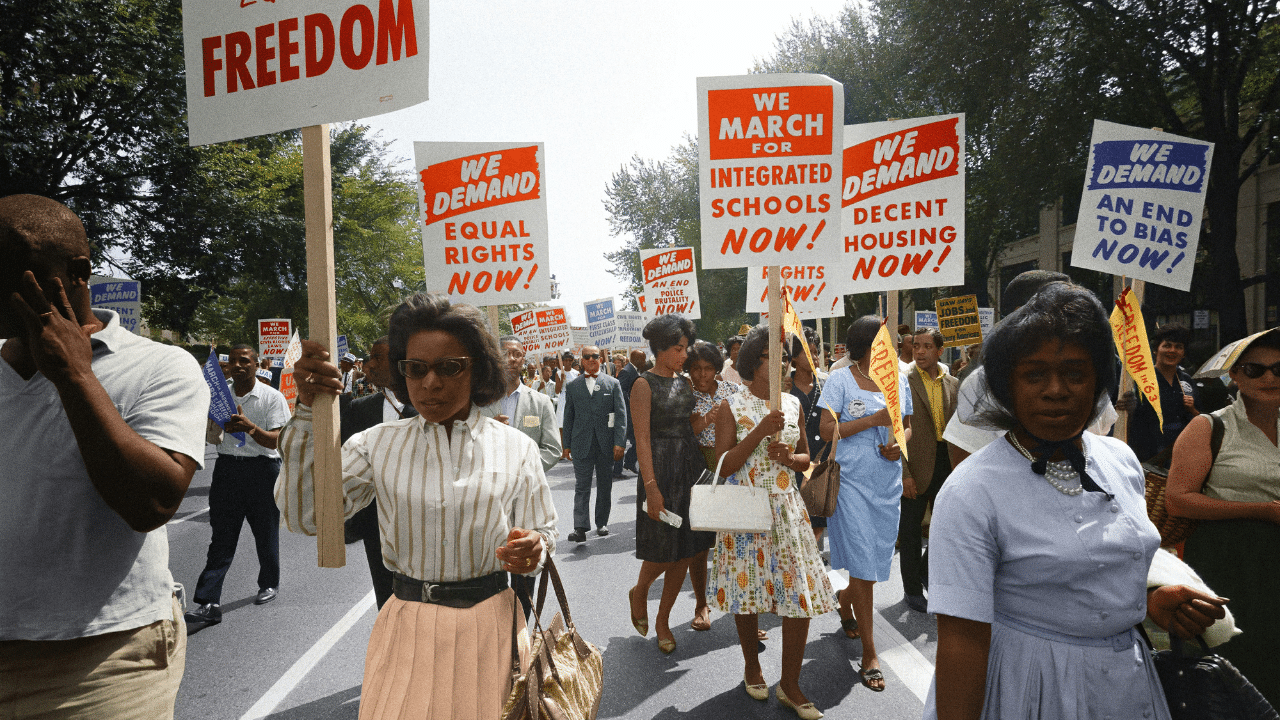

The Fourteenth amendment prohibited former Confederate states from repaying war debts and compensating former slave owners for the emancipation of their enslaved people. Under Section 5 of the amendment, Congress was granted the power to enforce its preceding provisions, which led to the passage of other federalism landmark legislation in the 20th century, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Former Confederate states were required by Congress to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment as a condition of their renewed federal representation.

What is the Reconstruction Era?

In the history of the United States, the Reconstruction Era is generally considered the post-Civil War period until the Compromise of 1877. The Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863 marks the beginning of the Reconstruction of the South, and Reconstruction Era Presidents include Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, and Ulysses S. Grant.

The Thirteenth Amendment is known as one of the “Reconstruction Amendments,” or “Civil War Amendments,” and was passed by the United States Senate on April 8, 1864, the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, and ratified by 27 of the 36 existing states on December 6, 1865. It was proclaimed on December 18, 1865. The other Reconstruction Amendments adopted during the Reconstruction of the American South after the American Civil War are the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, adopted between 1865 and 1870.

During Reconstruction, slavery was abolished throughout the entire nation, Confederate secession ended, and the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were ratified. The Reconstruction Era generated the familiar terms “carpetbaggers” to describe Northerners, and “scalawags” for white Southerners who supported Reconstruction efforts.

In addition to the three Reconstruction Amendments, many important laws were passed to provide freed former slaves with equal rights under the Constitution. Blacks were voting, taking political office, establishing integrated school systems, and forming integrated coalitions. Organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, the White League, and Red Shirts terrorized black Americans to drive them away from the polls, neighborhoods, schools, restaurants, and everywhere else. However, President Grant used federal power to shut down the KKK in the early 1870s.

Racially-motivated domestic terrorism was not the only lingering effect of the American Civil War. The country was torn by economic devastation. In the South, farms and their stocks were in shambles, the railroad system and the rest of the transportation infrastructure was in ruins. Restoring the infrastructure of the South became a high priority, but former slave owners in the South had little capital to pay the costs of restoration.

James W. Ely, Jr., The Oxymoron Reconsidered: Myth and Reality in the Origins of Substantive Due Process, 16 Const. Commentary 315 (1999).

WHAT IS THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT CITIZENSHIP CLAUSE?

The Fourteenth Amendment Citizenship Clause was aimed at settling definitively the lingering question regarding the citizenship of freed slaves, of which there had been much debate across the country following the American Civil War and Reconstruction. The Fourteenth Amendment therefore sought to put beyond doubt that “all persons, white or black, and whether formerly slaves or not, born or naturalized in the United States, and owing no allegiance to any alien power, would be citizens of the United States and of the state in which they reside.” Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884).

These provisions sought to foster a unity and expand a national consciousness following the strife of the American Civil War and the ongoing efforts of Reconstruction.

Children of foreign diplomats were therefore excluded from citizenship as their diplomatic immunity makes them subject to expulsion from the country as opposed to the jurisdiction of US Law. United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898). Similarly, Native Americans, owing allegiance to their tribe and not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, were originally excluded from birthright citizenship. This was later addressed by enactment of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 which established citizenship for all Native Americans previously excluded by the constitution.

The Citizenship Clause also confers birthright citizenship to children of Undocumented Immigrants born on United States Territory, a matter of some controversy among certain sectors seeking to limit perceived “Birth Tourism,” and “Anchor Babies.” There have been efforts to overturn these immigration provisions by legislation and executive fiat, but none have been successful and it is doubtful they would pass constitutional muster in the judiciary absent subsequent amendments.

WHAT IS THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT DUE PROCESS CLAUSE?

The nature and scope of the rights protected by the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments are among the most debated topics in all of constitutional law. As a central crux, Due Process protects against the arbitrary denial of life, liberty or property by the government. Although these clauses are identical, the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment applies to the federal government, while the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment extends these protections as applicable against the states. Courts have recognized these provisions encompass twin protections of Procedural Due Process and Substantive Due Process.

History of the Due Process Clause

When the Fifth Amendment was ratified in 1791, the phrase “due process of law” was understood to refer to matters of judicial procedure. The closely related phrase “law of the land” had a broader meaning, referring to existing law. Neither, however, encompassed what is now known as “substantive due process.”

By the Fourteenth Amendment’s enactment in 1868, the concept of due process significantly evolved through judicial decisions at the state and federal levels, and through both pro-slavery and abolitionist forces invoking due process in constitutional arguments over the expansion or prohibition of slavery. By 1868, the Supreme Court of the United States and the majority of state supreme courts, as well as the leading authors on constitutional law, embraced substantive due process.

What is Procedural Due Process?

Procedural due process imposes constraints on governmental decisions that deprive individuals of “liberty” or “property” interests within the meaning of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth or Fourteenth Amendment. In other words, some form of hearing or “procedure” is required before an individual is finally deprived of a property or liberty interest. Courts analyze the governmental and private interests affected when determining whether procedural protections were afforded in a particular situation.

The Supreme Court of the United States set forth three factors that normally determine whether an individual has received the “process” that the Constitution finds “due”: (1) the private interest that will be affected by the official action; (2) the risk of an erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and the probative value, if any, of additional or substitute procedural safeguards; and (3) the Government’s interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirement would entail. City of Los Angeles v. David, 538 U.S. 715 (2003).

To determine whether governmental action violates due process rights under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, courts assess whether the behavior of the governmental officer is so egregious, so outrageous, that it may fairly be said to shock the contemporary conscience. The “shock the conscience” standard is satisfied where the conduct was intended to injure in some way unjustifiable by any government interest, or in some circumstances if it resulted from deliberate indifference. Rosales-Mireles v. U.S., 138 S.Ct. 1897 (2018).

In Rosales-Mireles v. United States, the judge sentenced the defendant within the improper punishment range set by the Federal Sentencing Guidelines because the state actor probation officer who prepared his pre-sentence investigation report mistakenly included a prior misdemeanor conviction twice. On appeal, he argued a violation of his Fifth and Fourteenth Amendment right to due process of law. The Supreme Court of the United States reversed and remanded for a new sentencing hearing. Ensuring the accuracy of Guidelines determinations serves to prove certainty and fairness in sentencing on a greater scale, at little cost to the system by resentencing the defendant.

What is Substantive Due Process?

Substantive Due Process is a protection against government infringement on fundamental rights of the people. Substantive Due Process is distinguished from Procedural Due Process as the latter primarily concerns the process in the adjudication of the recognized interest while the former concerns the reach of legislation and consideration of those acts (fundamental liberties) that should remain beyond government regulation.

As the Supreme Court of the United States recognized in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, 505 U.S. 833, 846 (1992): “Although a literal reading of the Clause might suggest that it governs only the procedures by which a State may deprive persons of liberty, for at least 105 years, since Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U.S. 623, 660-661 (1987), the Clause has been understood to contain a substantive component as well, one ‘barring certain government actions regardless of the fairness of the procedures used to implement them.’” Daniels v. Williams, 474 U.S. 327, 331 (1986). Indeed, as Justice Brandeis recognized, “it is settled that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to matters of substantive law as well as to matters of procedure. Thus all fundamental rights comprised within the term liberty are protected by the Federal Constitution from invasion by the States.” Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357, 373 (1927). Substantive Due Process is therefore best understood as a bulwark “against arbitrary legislation,” Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, 541 (1961), that enshrines certain rights as fundamental liberties even though they are not enumerated in the Bill of Rights. “It is a promise of the Constitution that there is a realm of personal liberty which the government may not enter.” Planned Parenthood, 505 U.S. at 847.

There is some criticism and debate over the legitimacy of this doctrine, particularly among Constitutional Originalists like Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and the Late Justice Antonin Scalia, who called Substantive Due Process a “judicial usurpation.”

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several fundamental rights upon a reading and application of Substantive Due Process. For example, the Court ruled in Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965), that the Constitution does not permit a State to forbid a married couple to use contraceptives, finding a Right to Privacy in the “penumbra” of other constitutionally enumerated rights (concurring with the majority opinion, Justice John Marshall Harlan II even wrote that “liberty” encompassed the Right to Privacy). Similarly, the Court struck down a ban on interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), finding a fundamental liberty interest in marriage despite the fact it is mentioned nowhere in the Bill of Rights. Initial opinions revolved around contract regulations and freedom of contract.

The courts employ two primary standards of review when a Substantive Due Process violation is alleged. When government action infringes upon a fundamental right, the court employs “Strict Scrutiny,” the highest level of judicial review, which requires that the law be narrowly tailored and employ the least restrictive means of advancing a compelling government interest. For non-fundamental rights, the law must merely be rationally related to a legitimate government interest.

WHAT IS THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE?

In the wake of the American Civil War, Congress proposed and the States ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, providing that no State shall “deny to any person . . . the equal protection of laws.” To its proponents, the Equal Protection Clause represented a “foundation[al] principle”—“the absolute equality of all citizens to the United States politically and civilly before their own law.” Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess., 431 (1866) (statement of Rep. Bingham) (Cong. Globe). Soon-to-be President James Garfield observed, the Fourteenth Amendment would hold “over every American citizen, without regard to color the protecting shield of law.” Cong. Globe 2462 (statement of Rep. Garfield). Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 600 U.S. 181 (2023).

For more than a century, legal scholars have looked to the 1866 Civil Rights Act for clues regarding the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. Kurt T. Lash, Enforcing the Rights of Due Process: The Original Relationship Between the Fourteenth Amendment and the 1866 Civil Rights Act, 106 Geo. L.J. 1389 (2018). The Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause mandates that equally situated persons be treated equally under the law.

In Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the states from maintaining racially segregated public schools. This opinion overruled the “Separate but Equal” doctrine, invalidating decades of racial segregation of African Americans during the era of Jim Crow laws.

How is the Fourteenth Amendment different from the Thirteenth Amendment?

The Thirteenth Amendment differs from and is broader than the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause in two important respects. First, the Thirteenth Amendment does not have the limitation of the Equal Protection Clause—the Thirteenth Amendment applies to purely private conduct imposing either slavery or a badge or incident of slavery, which the Fourteenth Amendment only applies to state action. Carter, William M., Race, Rights, and the Thirteenth Amendment: Defining the Badges and Incidents of Slavery, 40 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1311 (2007).

What is the Batson rule?

The Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause prohibits excluding jurors from serving in a criminal jury trial solely due to their race. This has become a primary tenet of criminal procedure.

In Batson v. Kentucky, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in a landmark case that a prosecutor’s use of peremptory challenges to dismiss jurors from a jury trial without providing a valid reason was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment when the jurors were dismissed solely due to their race.

WHAT IS THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT PRIVILEGES OR IMMUNITIES CLAUSE?

The Privileges or Immunities Clause is found in Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, stating:

“No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

The clause was designed to protect the fundamental rights of citizens and ensure that states couldn’t infringe upon these rights. However, the Privileges or Immunities Clause has not been interpreted as extensively and broadly as some other parts of the Fourteenth Amendment, and its scope and application have been the subject of legal debate.

Thus the impact of the Privileges or Immunities Clause has been limited in certain cases as the Courts have often relied on the Equal Protection Clause and the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to address issues related to individual rights and state actions.

What are the Slaughterhouse Cases?

The Slaughter-House Cases were a consolidation of several cases which minimized the impact of the Privileges or Immunities Clause on state law. The Supreme Court of the United States, narrowly interpreting the Privileges or Immunities clause, held that it only protected a limited set of national rights, such as the right to travel, access federal courts, and protection on the high seas.

WHAT IS THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT INCORPORATION CLAUSE ?

The Fourteenth Amendment’s Incorporation Clause is what applies the protections of the Bill of Rights to the individual States. The relevant portions of section I of the Fourteenth Amendment read:

“. . . nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The Incorporation Clause finds its premise in the words “nor shall any State,” the idea being that Bill of Rights protections, which originally only applied to federal government actions, are extended to the states through this language in the Fourteenth Amendment. Therefore, the States are prohibited from violating fundamental rights that are protected by the federal Constitution.

This legal doctrine has been established through a series of Supreme Court rulings over the years. For example, Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925) incorporated the First Amendment Freedom of Speech and Freedom of the Press provisions against the states. Similarly, Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), incorporated against the states the Sixth Amendment Right to the Assistance of Counsel for all felony cases and Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) incorporated the Fifth Amendment Privilege against Self Incrimination.

These and many other rulings played crucial rules in extending various constitutional liberties to the states under the Incorporation Clause. As a consequence, much of the guarantees of the Bill of Rights are equally applicable to State and Federal governments.

WHAT ARE THE OTHER CLAUSES OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT?

The second, third, fourth, and fifth sections of the Fourteenth Amendment are seldom litigated and have thus lacked the first section’s impact on constitutional jurisprudence.

Section 2 establishes the consequences for states that deny or abridge the right to vote (suffrage) to male citizens over the age of 21. Essentially, it proportionally reduces a state’s representation in the U.S. House of Representatives if the state denies or limits an eligible male citizen’s right to vote. This measure was intended to penalize states who continued disfranchisement of eligible voters, specifically former slaves who had just been granted citizenship and the right to vote.

Section 3 disqualifies from public office those who, having previously taken an oath to support the constitution, rebelled or engaged in insurrection against the United States government. This measure was implemented in response to unrepentant former confederates serving as senators and representatives in the United States Congress following the Civil War. In recent history, it was invoked to prevent former President of the United States Donald J. Trump, and others who participated in the January 6th United States Capitol attack, from seeking or serving in public office.

Section 4 of the Fourteenth Amendment was implemented to settle the issue of Debts incurred during the Civil War. It emphasizes the legitimacy of U.S. government debt while explicitly repudiating any debts incurred by the Confederacy during the Civil War, stating that debts related to insurrection or the support of slavery would not be honored.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provides the crucial authority granting congress the power to pass laws necessary to enforce the rights and protections of the Amendment.

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

The Fourteenth Amendment is considered among the most consequential amendments to the United States Constitution, safeguarding the civil and political rights of the people. Debated and enacted in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the Fourteenth Amendment sought to preserve the rights and equal treatment of those individuals within the jurisdiction of the United States, including former slaves, and provide a discernable framework for Reconstruction. This amendment addressed suffrage, Equal Treatment Under Law, Due Process of law, established citizenship and naturalization rights, and generally sought to settle and rectify certain errors of the Confederate States of America. The Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Treatment and Due Process Clauses are among the most litigated constitutional provisions with continually evolving jurisprudence and doctrine. Additionally, the events of the January 6th United States Capitol attack have provided renewed significance to the Disqualification from Office for Insurrection or Rebellion Clause in section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT COURT CASES

The Supreme Court of the United States has interpreted and applied the Fourteenth Amendment since its ratification in 1868, with many opinions considered landmark civil rights cases.

- In Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court of the United States found that a Texas law outlawing sodomy, and effectively same-sex sexual intercourse, violated the Right to Privacy.

- In Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the fundamental Right to Marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- In Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, the SFFA filed lawsuits against Harvard and the University of North Carolina, arguing their race-based admissions programs violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Constitutional Amendment. The Supreme Court of the United States agreed.

- In Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado, the Supreme Court of the United States reiterated the “central purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate racial discrimination emanating from official sources in the State.” In this case, the Justices enforced the Constitution’s guarantee against state-sponsored racial discrimination in the jury system.

- In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court of the United States overruled Roe v. Wade, its progeny, and decades of judicial precedent recognizing women’s reproductive rights and a fundamental Right to Abortion. This decision marked the first time the court invalidated a previously recognized constitutional right, and exhibited a willingness from certain members of the Court to revisit settled Due Process doctrine.

Which statement best describes the Fourteenth Amendment?

Perhaps the most eloquent presentation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantees is in Poe v. Ullman with Justice John Marshall Harlan II providing his encompassing views of “Liberty” in his dissent to the majority opinion:

[T]he full scope of the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause cannot be found in or limited by the precise terms of the specific guarantees elsewhere provided in the Constitution. This ‘liberty’ is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints . . . and which also recognizes, what a reasonable and sensitive judgment must, that certain interests require particularly careful scrutiny of the state needs asserted to justify their abridgment.